Okay, I get the message. Good thing it doesn’t apply to me—I never correct anyone’s grammar unasked, except in this blog.

Of course, you’re welcome to ask…

Okay, I get the message. Good thing it doesn’t apply to me—I never correct anyone’s grammar unasked, except in this blog.

Of course, you’re welcome to ask…

My wife and I are interested in learning to weld, and as part of our research, we checked out a site that advertised welding lessons. The site has a good example of how not to use separable verbs, so I wrote him about it. I spent enough time on the email that it’s worth including here. The subject line was “We might order your materials… .” Here’s what I wrote:

…and thank you for the free sample. My wife and I plan to read it carefully.

When you first setup your MIG machine you’ll have to feed this wire through the rollers.…As far as setup goes, that’s about all there is to setting up a MIG welder, and that’s why they’re so great for beginners.

I suppose you could say that English became a lot more cosmopolitan in 1066 when the Normans invaded and infused French into the language. From them we got “pork” and “beef” on the dinner table and “pig” and “cow” in the barnyard. But English, over time, has become almost a pidgin language from all the loan words it has acquired. Hence the humor of this Making It:

He’s making fun of people who have a provincial attitude and don’t give newcomers enough time to learn the language.

It’s a good point, though:

If you go to visit a place where the people speak something other than English, make an effort to learn that language!

Not sure that manager should be smoking in the workplace, either…

The article I criticized in the previous post has its share of good examples, too. The article is by Dan Geer from the Hoover Institute; it’s 20 pages of difficult reading about computer security, but it’s good if you’re into that sort of thing. Here’s the sentence that a lot of people get wrong, but they don’t:

Per the present author’s definition, a state of security is the absence of unmitigatable surprise—there will always be surprises, but the heavy tails that accompany complexity mean that while most days will be better and better, some days will be worse than ever before seen.

Of late, we have come to center our strategy on employing algorithms to do what we cannot ourselves do, which is to protect us from other algorithms.

This post pulls out a mistake from an essay from the Hoover Institute that is heavy-duty reading. If you’re looking for something with more, um, substance than your average internet article (Heavier than even something from Scientific American), go read it. It’ll take a while. It’s about system security (such as computers, national infrastructure, and so on) and it’s good. Here’s the link. Don’t say I didn’t warn you.

https://www.hoover.org/research/rubicon

Now having said all that, they spoil it (okay, some of it) by making an elementary error in grammar that introduces an ambiguity into something that ought not be ambiguous. The article is hard enough to follow already, (and most of the writing is actually fairly well done) so we don’t need more difficulties. Here’s the bad passage:

In the absence of purposeful disconnectedness at critical points, the mechanics of complexity then take hold so that we undergo “a switch between [continuous low grade volatility] to . . . the process moving by jumps, with less and less variations outside of jumps.”

Should that be “less and less variation,” or should it be “fewer and fewer variations”? At least they’re quoting someone else (Nassim Nicholas Taleb, “The Long Peace is a Statistical Illusion,” accessed January 23, 2018, http:// docplayer.net/48248686–The–long–peace–is–a–statistical–illusion.html), but they need to fix the grammar here so we have at least a chance to know what they mean.

I mentioned this error a couple times in the past. Here’s one link: http://writing-rag.com/1863/another-lesson-about-less-and-fewer/ You can find a few more if you do a search in the upper right corner of the page.

This Real Life Adventures comic makes my exact point today:

In high school I read a book titled How to Lie with Statistics, and this was one of its points. Here’s the rule:

When you mention a comparison, say what you’re comparing to!

If someone says, for example, “My product is better!” Ask: Better than the competition? Better than it used to be? Better than the worst similar product? Better than the reviewers say it is? Better than a first grader could do?

The point of expository writing is to explain things, so don’t leave your reader guessing.

Commas are useful punctuation marks. They serve to separate, and they show a weaker separation than semicolons, which are weaker than periods. We’re familiar with commas separating the parts of compound sentences and the parts of lists. Commas are used for another kind of separation, and I’m not sure what to call it. Here’s part of a sentence:

“If we do end up finding something that’s good,

I’ll stop there for a moment. What’s good here? It looks like something is good, right? But when you see the rest of the sentence, you discover that it’s the finding that’s good!

“If we do end up finding something that’s good, but even if we don’t find anything, that works as well,” says Marco Bortoletto, one of the archaeologists on the team.

We should have a comma after “something” so we can tell that what’s good isn’t the something. That’s the separation I’m writing about. Beyond representing a pause in spoken language, I’m not sure what to call it. Sorry.

So here’s how the sentence should be written:

“If we do end up finding something, that’s good; but even if we don’t find anything, that works as well,” says Marco Bortoletto, one of the archaeologists on the team.

Notice that I changed the comma after “but” to a semicolon. It’s a good idea to use a semicolon to separate the parts of a compound sentence if the parts have their own commas. But that’s another lesson.

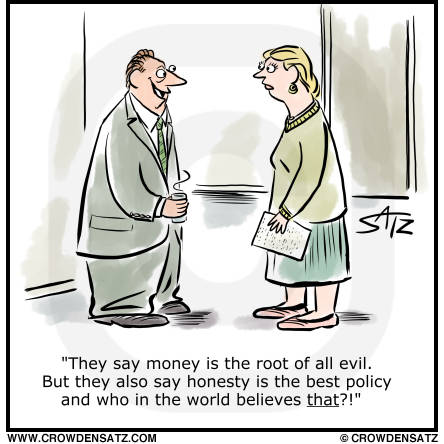

It’s the LOVE of money that’s the root of all evil. (I Tim. 6:10) Harrumpf.

Seems I can’t resist Darren Bell’s Candorville comics in which the protagonist, who is a writer, interrupts and corrects someone’s grammar. Here’s another one. I think I make this mistake myself sometimes. After all, can “read” have both an active and passive meaning?

Or “them,” in this case.